Feature

Who Neu?

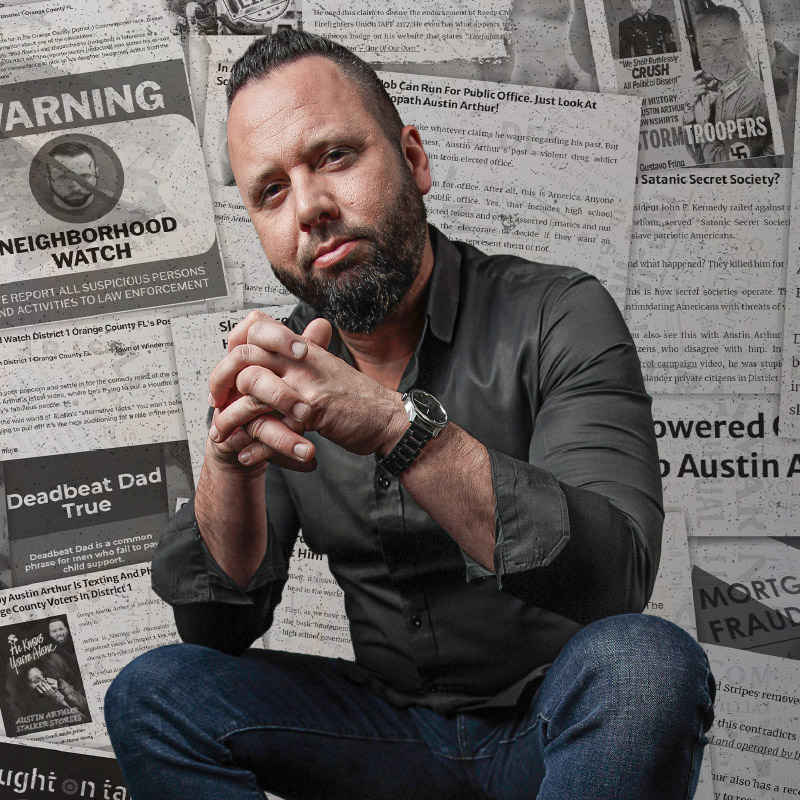

Long before he had the language for it, Adam Markowitz knew he was different. Helping others became the moment he finally understood why.

- Heather anne lee

- Fred Lopez

There’s a moment near the start of my first conversation with Adam Markowitz when I realize I’m watching a man meet himself—in real time, right in front of me. I don’t mean metaphorically or mystically. I mean literally: his eyes dart to the corner of the room every time there’s a small sound. His foot taps. His shoulders rock in a soft, unconscious rhythm, like he’s keeping time with something only he can hear. And his fingers—my God, the man could fidget a hole into granite.

“I just want to know why,” he says, not with frustration, but with something gentler. Something that sounds like a sigh he’s been holding for decades. “Why fireworks make me want to crawl out of my skin. Why social stuff drains me for days. Why I’ve spent my entire adult life thinking everyone else knows some secret manual to human interaction that I somehow missed.”

He doesn’t say it with despair. More like curiosity. More like a man who has lived long enough to accept that maybe the call is coming from inside the house.

And there it is, the thesis of his life, the one he didn’t know he’d been writing: You are never too old to learn something beautifully new about yourself.

Adam says it the way some people talk about their faith. His humor always arrives a few seconds before his vulnerability, like a scout checking to see if the coast is clear.

The Boy Who Thought His Way Through Life

Before he became a man who quotes tax law with the softness of someone reciting bedtime stories, Adam was a Florida kid who lived almost entirely in his head. The world was too loud. Too bright. Too much. But, like most gifted kids of his generation, nobody considered words like sensory processing or autism. If you were bright, you were fine. If you were anxious, you were dramatic. If you rocked back and forth while talking, you were told to “stand still, for the love of God.”

His father was the first person who ever truly got him, though they’d never have said it that way. They weren’t a Hallmark-card duo; they were a mismatched comedy team, a father and son bonded by Scrabble games, questionable sports attempts, and an affection so rough-edged it squeaked when they turned it.

When Adam tells me his dad was his best friend growing up, he does it in that brave way people speak when nostalgia still stings. “When we moved down here, I didn’t have any friends for years,” he says. “It was just me and my dad.”

They became a two-person ecosystem: dinners out, sports fields, long car rides filled with the meaningful silence of people who love each other but aren’t fluent in sentiment. Adam still keeps a Scrabble board in the trunk of his car. Not as symbolism. Not for metaphor. Because he sincerely might need it. This is a man who needs a board game the way some people need a Xanax.

He tells me about the day he beat his dad for the first time. He was maybe 13. The earth briefly rotated in the opposite direction. His father took one look at the board, exhaled like a man accepting his fate, and said, “I can’t ever play you again.”

“He wasn’t mad,” Adam says. “He was… proud. But we never played again.”

His father had a knack for emotional whiplash. Like at Adam’s Bar Mitzvah, which should have been a moment for ancestral blessing, maybe a whispered bit of generational wisdom. Instead, he put a hand on Adam’s shoulder, looked him dead in the eye, and said: “Son, you ain’t a man until you start paying taxes.”

This is not a man who traffic-lights his parenting style.

Even now, though they no longer speak—a backstory built on business splits and emotional stalemates Adam tells with a painful kind of pragmatism—his father hovers in the background of every memory. An absence that sits next to him like a third chair in every story.

He calls him a “crotchety old man” but with the tone of someone holding up a prophecy more than an insult. “I told my wife, I’m trying so hard not to become him,” he says. “But I see it. I see the gravitational pull.”

Adam still keeps a Scrabble board in the trunk of his car. Not as symbolism. Not for metaphor. Because he sincerely might need it. This is a man who needs a board game the way some people need a Xanax.

The Sensory World He Couldn’t Name

The signs were there before he could talk.

The way he recoiled from fireworks—terrified, not startled.

The sports arenas that sent him spiraling.

The constant fidgeting.

The endless rocking.

The exhaustion after “peopling” for longer than 45 minutes.

“I used to think I was just brilliant. I mean, my mother told me that, so it had to be true,” he says now, laughing at the memory of his certainty. “Turns out I was brilliant and missing every social cue possible.”

Arena football games were a family outing. He remembers the bright lights, the pyrotechnics, the inflatable mascots bouncing across the field. But mostly he remembers this icy, internal horror that he thought everyone else felt and simply coped with better.

“I won’t go outside on the Fourth of July,” he tells me. “My dog doesn’t need the thunder shirt. I do.”

He isn’t being dramatic. His body simply does not operate on the same frequency as the world’s noise.

But back then, he was gifted. Academically sharp. Verbally nimble. He could explain a geometry concept better than he could make eye contact. Back then, that combination tricked everyone—including himself—into thinking everything was just fine.

Making Up the Difference

Adam’s childhood was one long sprint of trying to make his brain line up with the world around him. He was terrible at sports—spectacularly, heroically terrible—yet his father kept signing him up, hoping the athletic gene would spontaneously activate like a dormant volcano.

“Spoiler alert: It didn’t,” he laughs.

Adam couldn’t hit a baseball to save his life. He could, however, see the whole field, predict the whole play, and coach every kid around him better than he could swing a bat. He could think his way through anything—sports included.

“I was basically a 14-year-old coach,” he says.

What he did have—the thing that made him feel big in all the ways he wasn’t physically—was music.

Band became his refuge. Trumpet, first chair. A place where the rules didn’t shift under his feet and the rhythms made sense in a way people never quite did. And when he found marching band, something clicked: here was a world where precision was love, where patterns were language, where leadership had nothing to do with charisma and everything to do with competence.

He and his friends Craig and Chris held down the trumpet line like a little brass monarchy—three kids trying to make sense of themselves one rehearsal at a time. For years, Adam sat in that first chair like it had been tailor-made for him, until the very last audition of his senior year when Craig finally beat him.

Once.

The only time.

“Devastated,” Adam says. “I mean, I was never supposed to lose. Ever.”

He laughs now; Craig is a client. They still treat that one audition like the great family feud that never actually happened. But the truth is, that moment mattered. It softened something sharp in him. It taught him that leadership isn’t about staying on top; it’s about what you build for the people coming behind you.

That’s really where the Adam we know began: in the brass section, in the late-night bus rides home, in the quiet sense that legacy isn’t about spotlight but continuity.

And maybe that’s why the idea of forever has always unnerved him. He’ll tell you he’s not afraid of dying—“that part seems easy,” he shrugs. What rattles him is what comes after. The eternity part. The no-end part. The part you can’t understand or prepare for or rehearse until it’s perfect.

Maybe it came from being raised by a Jewish father and a Catholic mother—two religions with wildly different user manuals and equally dramatic afterlives. Or maybe it was simply his wiring, the way uncertainty skews toward terror when your brain likes clean edges.

“I’m not scared of death,” he says. “I’m scared of the infinite. The part nobody can explain. The part with no exit ramp.”

He says it in the same tone someone else might use to admit they’re afraid of snakes—matter-of-fact, slightly embarrassed, but absolutely serious.

The Collapse and the Pivot

His adult life began with a collapse disguised as a math class.

He wanted to be a meteorologist. Wanted it so much he could taste it. But when the numbers turned into letters, the whole thing fell apart.

The first time he took the class, he got a D.

The second time, he failed.

Brutally.

Concretely.

With no room for interpretation.

“It destroyed me,” he says. “I thought brilliance was enough. It wasn’t.”

He switched majors six times. Graduated with a 2.3 GPA. Landed degrees in music and history—beautiful, useless things that opened approximately zero doors.

He worked hotel night audit shifts, asking for raises he didn’t get. He moved back home—not from necessity, but from a yearning to understand the life his father lived, the grind he respected but didn’t yet comprehend. His father was elated. His mother, not so much.

He calls those years humbling. Useful. Quieting.

The emotional equivalent of sanding down sharp edges.

Love was another series of socially awkward detours until he met Elizabeth in 2010. She grounded him. Challenged him. Saw him.

“She gave me a sense of stability I didn’t know I needed,” he says. “I didn’t know I needed anyone to see me clearly because I didn’t see myself clearly.”

“It explained everything. Why I hated fireworks. Why I couldn’t just ‘relax.’ Why my brain felt like a machine with its own operating manual. Why I never fit the shape people expected me to.”

The Long Road to Diagnosis

Most people don’t wake up at 40 and decide to get tested for autism unless a quiet truth has been tapping on the inside of their skull for years. Adam had felt that tap—a rhythmic knock, really—long before he ever said the word out loud. He’d scroll through videos from autistic creators late at night, the kind who talk with startling clarity about sensory overload, social fatigue, the comfort of rigid routines, the need to fix something right now because otherwise the world feels slightly tilted.

“I’d watch these videos and think, ‘Oh shit… that’s me,’” he says, with the tone of a man discovering he’s been the plot twist in his own story.

But he refused to self-diagnose. Guessing wasn’t his thing. Accuracy was. If he was going to do this, he wanted the truth, not the internet’s version of it.

So he began researching the way some people plan weddings—compulsively, obsessively, spreadsheet by spreadsheet. He called specialists who evaluated adults. He compared methodologies. He read actual academic papers, the kind written in a dialect of English reserved exclusively for people with doctorates and patience. The more he learned, the more the pieces lined up, and the more the question pressed: What if this is it? What if this explains the whole damn mosaic?

He booked an assessment for October. Five months of waiting, which, for someone wired like Adam, felt less like anticipation and more like being trapped in a dentist’s office without an appointment time.

When the day finally came, he braced himself for a clinical scene—fluorescent lights, a clipboard, maybe even one of those interrogation mirrors where you assume someone in a suit is judging your posture. Instead, he stepped into what looked like a converted living room: soft lighting, neutral walls, no sensory attack, no cold surfaces. The kind of place designed for people who never quite feel at ease in the world.

Before the real testing began, they gave him a pre-screening—150 questions that read like someone had been taking notes on his life:

Do certain sounds overwhelm you?

Do you find small talk exhausting?

Do you fixate on details?

Do you need routines to function?

Do you notice patterns others miss?

He checked boxes he didn’t realize belonged to him.

Then came the main event: six hours of cognitive testing that felt like a triathlon for the mind. Spatial reasoning tasks where he had to fold shapes in his imagination. Pattern-recognition puzzles that could double as geometry if geometry had been invented by a surrealist. Memory sequencing drills. Logic problems where every option looked like a setup for failure.

And then there was the language test.

“They asked me to list as many words as possible starting with a certain letter,” he says. “So I just started with every two-letter word I know. Then every three-letter word.” He shrugs. “It felt like training for the Scrabble Olympics.”

It wasn’t just math and words and puzzles. The assessment dug deeper, in ways he hadn’t fully prepared for. They talked about his childhood, the way fireworks felt like physical pain, why crowds drained him to the bone, the decades of emotional misfires—him misreading others, others misreading him. It was, as he puts it, “like turning my whole life inside out and inspecting the stitching.”

When the results arrived, the diagnosis was official: Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Not a shock. But something gentler—relief, recognition, the sudden easing of a lifelong tension he hadn’t known was clenched.

“It explained everything,” he says quietly. “Why I hated fireworks. Why I couldn’t just ‘relax.’ Why my brain felt like a machine with its own operating manual. Why I never fit the shape people expected me to.” He pauses. “It made my whole life… make sense.”

And then, almost as an afterthought—though it isn’t one—another truth surfaced: Adam had already built a neurodivergent-friendly company years before he ever knew he was designing it for himself. He’d instinctively created systems for clarity, quiet, predictability, and fairness—because those were the things he needed, even before he understood why.

The diagnosis didn’t change who he was. It simply illuminated the architecture he’d been living in all along.

Naming it didn’t confine him. It freed him. He didn’t become the man he once imagined. He became someone far more layered… A man fluent, at last, in the language of his own mind.

The Business That Made Space Before He Did

Long before he knew the word autistic applied to him, Adam recognized something in the world that he couldn’t name. Anxiety that wasn’t laziness. Distraction that wasn’t disrespect. Emotional reactivity that wasn’t immaturity.

He saw it because he was it. Even if he didn’t know that yet.

The turning point came when he read about Rising Tide Car Wash down in South Florida—a family-run business built specifically to employ and empower autistic adults. The story hooked him. Here was a model that didn’t just “accommodate” people; it elevated them. Then he devoured the book The Power of Potential, the behind-the-scenes account of how Rising Tide reimagined an entire workplace by building around strengths instead of deficits.

“It blew my mind,” he says. “Not in a ‘this is cute’ way, but in a ‘why aren’t we all doing this?’ way.”

So he stole the good parts—unapologetically—and began reshaping his own company long before he had any inkling that the systems he was building were the very systems his own brain needed.

The program is still in its infancy, but it’s a program nonetheless. 2026 being his sixth neurodivergent hire in two years.

And he’s slowly building a workplace that quietly, steadily, unmistakably made room:

Noise-canceling headphones.

Clear, unambiguous task lists.

Structured work cycles that didn’t punish different rhythms.

Breaks whenever someone hit sensory overload—no questions, no side-eye.

Fidgets spinners.

Permission to work in silence.

Permission to work in bursts.

Permission to work like a person instead of a machine.

“If you feel successful at the end of the day,” he tells his team, “that’s the win. I don’t need perfection. I need progress.”

He thought he was designing it for them.

He didn’t realize he was also building a sanctuary for himself.

Or that he was laying the scaffolding for a legacy—one that celebrates minds like his decades before he ever put a name to his own.

That’s the strange grace of finally understanding yourself: the moment you do, you suddenly see everyone else more clearly too.

Understanding, At Last

At 40, Adam Markowitz finally understands why his brain has always run on a slightly different operating system. He still rocks when he thinks. He still fidgets. He still avoids fireworks with the commitment of a man dodging an ex. He still keeps a Scrabble board in the trunk like other people keep spare tires. Now he knows why.

And naming it didn’t confine him. It freed him. He didn’t become the man he once imagined. He became someone far more layered—funny, anxious, brilliant, sideways-thinking, self-aware, occasionally infuriating, endlessly curious. A man fluent, at last, in the language of his own mind.

He learned that difference isn’t a flaw but a lens. That understanding himself helps him understand others. That the architecture he built for his team was, unknowingly, the architecture he needed too.

And maybe that’s the real legacy he’s building.

Not a business.

Not a title.

Not a story about overcomingBut a story about understanding.

About empathy.

About permission.

About learning yourself—finally, fully, without shame.

Because the truth is this: You are never too old to discover who you’ve been all along